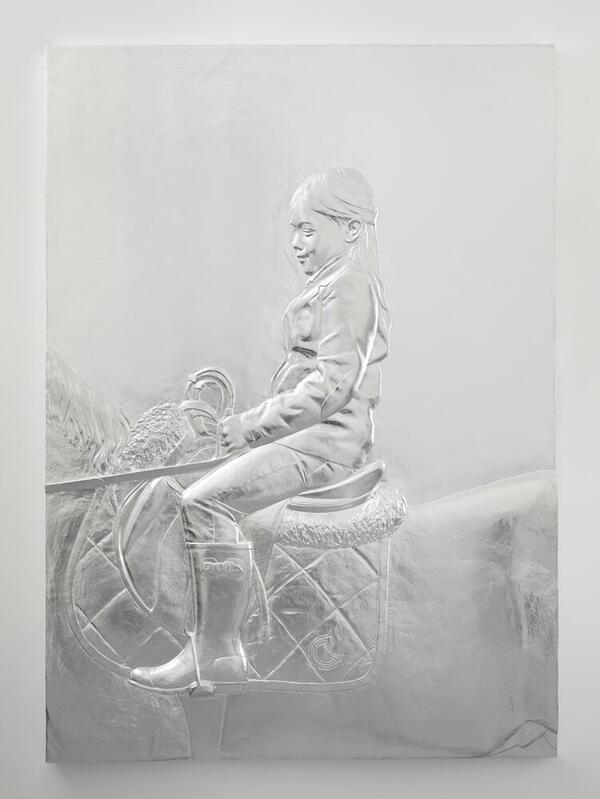

Horse & Rider

Horse and Rider, 2014 Acier inoxydable Pinault Collection

278 × 102 × 269 cm

A sculpture of the artist mounted on a horse, Horse and Rider is reminis-cent of the classical figure of the equestrian statue, in the tradition of the “canon” invented in antiquity: the Emperor Marcus Aurelius in the Capitoline Square in Rome, multiplied during the Renaissance through the honorary representation of the condottiere (military leaders), such as Donatello’s Gattamelata in Padua or Verrochio’s Colleone, in Venice. As usual, Charles Ray uses the model closest to him, the easiest to call upon: himself. Paris is punctuated by these same sculpted groups representing saints and kings on horseback: from Bosi’s Louis XIV, in the nearby place des Victoires, to Bernini’s Louis XIV in the cour Napoléon in the Louvre, from Lenot’s Henri IV standing in the middle of the Pont Neuf to the Jeanne d’Arc on rue Castiglione, to name but a few. Like a subversion of this statuary of power and magnificence, Horse and Rider reverses all its codes, chipping away at the mani-festo of assurance and virility usually deployed by the genre. Instead of a haughty figure, in majesty and in movement, the figure of the artist, seated and stooped over his horse at a standstill, seems to be powerless: “I’m not a horse rider and the horse knows it. I tried to sculpt my nervousness and the horse’s as well” (from the catalogue of the Kunstmuseum, Basel, 2014). And for good reason: the artist did not sculpt the reins, which normally allow the rider to direct their mount. This image calls for another, that of a possible artist’s self-portrait, a pictorial one: the portrait of Watteau as Gilles, a disenchanted entertainer.

Horse and Rider does not commemorate any battle, nor does it celebrate its model. As is often the case with the artist, it is about questioning a “type” from the history of sculpture, in order to better account for their aesthetic value over time: “I see the great archaic or classical sculptures as contemporary. They work too well to be discarded or out-dated, regardless of the work’s original purpose. Horse and Rider, placed on the ground—not on a pedestal—interacts directly with the space of the viewer, with the public, with the city.

Finally, the work has as much to do with the personal history of the artist, who spent his adolescence in a particularly strict military high school, as with that of America, whether it be patriotic sculpted groups, Hollywood films, the Wild West and its mythical figure—the cowboy on horseback—or children’s figurines. The man on the horse conjures up an incredible iconography, a historical density to which the artist responds by the weight of the work itself, close to ten tonnes. Firmly embedded in the space, and a central tenet in multiple traditions of representation, the equestrian statue here sees the opening of a new chapter in its history, in which splendour gives way to the anti-hero, the modern Don Quixote.

“My sculptures circle the second floor, and in front of the Bourse is ano-ther portrait of an artist, myself, over the hill, sitting in a western saddle on a horse that is also over the hill. We are both exhausted, but rather than being up in the sky embedded in the clouds on a stone pedestal a mile high, we stand on the ground with you and your neighbour. [Rather than remaining superficial, the] patina of the city will have embedded itself within its surface rather than upon it. Be patient, Parisians.”

Charles Ray

Extract from the essay “57,000 Pounds” in the exhibition catalogue